Flipping through a Chinese dictionary one day, I found a definition for pistachio that had nothing to do with the nut. In Chinese, if someone calls you a pistachio, they mean that you’re as happy as a clam.

The Chinese language is filled with colorful idioms. These derive from popular folktales, local customs, historic episodes, and many other sources. Many are relatable to phrases in other languages, and it’s fascinating to see how different cultures express the same ideas in different ways.

For example, in English we refer to a favorite person as the “apple of my eye,” but in Chinese the favorite person is the “pearl of my palm.” What in the West we mean by a “land of milk and honey,” Chinese call a “land of fish and rice” (and, indeed, Western cuisine is often sweeter than Chinese!). I guess this proves that “every turnip has its hole”—meaning to each his own.

Measuring Up

Now think hard. Who’s the most talented person you can think of? An artist, a chef, a mathematician, a famous athlete, or perhaps a dancer? And just how gifted is this prodigy when measured... in liters?

It’s story time!

The brilliant Three Kingdoms Period statesman Cao Cao (pronounced “tsaow tsaow”) fathered three sons, each impressive in his own way. The youngest of the trio was Cao Zhi (“tsaow jhr”).

Cao Zhi had always been dad’s favorite in spite of many shortcomings. He was a heavy drinker, had poor self-discipline, and was terribly rash. Interestingly, he also happened to be a literary genius.

On the other hand, firstborn Cao Pi (“tsaow pea”) was greedy for power and cared little about his brother. Long aware of the possibility that he would be passed over and not inherit his father’s power, he took advantage of every situation to oust little brother from favor.

On the eve of Cao Cao’s death, after considerable deliberation, the aged statesman finally did bequeath power to his eldest. Still jealous and insecure, Cao Pi itched to get rid of his brother for good. He couldn’t do it directly though, as that would be somewhat frowned upon. So he came up with a ploy.

After his father passed away, the younger Cao Zhi, in true Cao Zhi fashion, drank himself tipsy, and completely missed the funeral. Seeing his chance, Cao Pi hauled his brother into court and laid down the conditions of his punishment: Compose a poem in the time you take seven strides, or pay with your life. The topic? “Brotherhood.” Oh, and you can’t mention the word brother even once in the poem. Go!

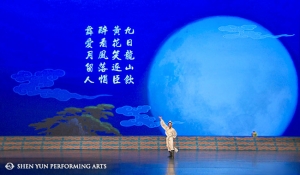

Cao Zhi, master of metaphor, then spouted these verses:

The beans were boiled to make a soup

And beanstalks fed the cauldron's flame

The beans lamented as a group:

You stalk, you know our root's the same,

So why do you to torture stoop?

Staggered no less by sentiment than awe, Cao Pi let little bro off.

Pithy yet potent, “Quatrain of Seven Steps” became Cao Zhi’s most famous work. In time, Cao Zhi, who had written spectacular essays at age 10 and could recite over 10,000 lines of poetry by 20, became a representative poet of his time just like his statesmen-warlord dad. Throughout the dynasties till today, some two millennia later, both have been venerated as masters of the art.

One scholar later wrote that if there were 100 liters of talent among men, 80 belonged to Cao Zhi (perhaps an ancient version of the Pareto principle’s 80/20 rule). This gave rise to the idiom “eighty liters of talent,” cái gāo bā dǒu (才高八斗), meaning someone who is extraordinarily talented.

Terms of Talent

Here are some other talent-related idioms, ordered from greater to lesser:

“Celestial generals and troops” (天兵天將, tiān bīng tiān jiàng): invincible, superior forces.

“Three heads and six arms” (三頭六臂, sān tóu liù bì): very resourceful, superhuman.

“Crouching tiger, hidden dragon” (藏龍臥虎, cáng lóng wò hǔ): hidden talent.

“Half-bottle of vinegar” (半瓶醋, bàn píng cù): half-baked, dilettante.

“Not a drop of ink in him” (胸無點墨, xiōng wú diǎn mò): unlearned, not cultured.

“Two hundred and fifty” (二百五, èr bǎi wǔ): ignorant, dope.

Curious for more? More idiom stories coming soon!

Betty Wang

Contributing writer

May 26, 2016