Recorded on tour while performing in Nashville, TN.

What’s red and white and rode all over? The answer hides in a traditional Chinese idiom: 馬到成功 (mǎ dào chéng gōng). It's a figure of speech meaning “instant success,” that literally means: “horses arrive, and with them success.”

Horsing around is serious business, or at least it was in ancient China. From battlefields to banquet halls, from mundane tasks to mythical tales, horses honed their talents under the spotlight of Chinese history.

Warhorses

During the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E-220 C.E.), China was often at war with neighboring nomadic tribes, especially the Xiongnu to the north. The Xiongnu, also known as the Huns, commanded a terrifying force on horseback that the imperial forces could only equal with cavalry of their own.

Unluckily, the emperor's lands in eastern China were more fit for growing rice than raising horses, and so the imperial cavalry had to import its warhorses—oftentimes from nomadic tribes that were allies of the enemy Hun.

By 104 B.C.E, the Han-Hun war had raged on and off for three decades, and Emperor Wu of Han had seen enough. He sent a massive military campaign to Ferghana (in Central Asia, nearly 3,000 miles away), armed with gold and soldiers, to purchase its famed Ferghana horses.

These horses were stronger, swifter, and bigger than any Chinese horses; they were the finest mounts then known. Adding to their mystical appeal, they had an odd habit of sweating blood when running, and were coined “flying” or “heavenly horses.”

Unfortunately, the King of Ferghana was such a horse-lover that he refused to sell his steeds. Harsh words were exchanged, and negotiations quickly soured after this king executed the Chinese ambassador. The four-year battle that ensued went down in history as the War of Heavenly Horses, with Emperor Wu’s troops emerging victorious. They left Ferghana to journey back to China with 3,000 horses—of which only 1,000 survived the trip—to continue fighting the Xiongnu for another decade. (To make a long story short, they won that war, too.)

Efforts to successfully breed these prize horses had mixed results back home, so regular imports were necessary to keep the herd alive. Successive rulers exchanged both silk and tea for horses along an extensive trade route that grew to become known as the Silk Road.

Dancing Horses

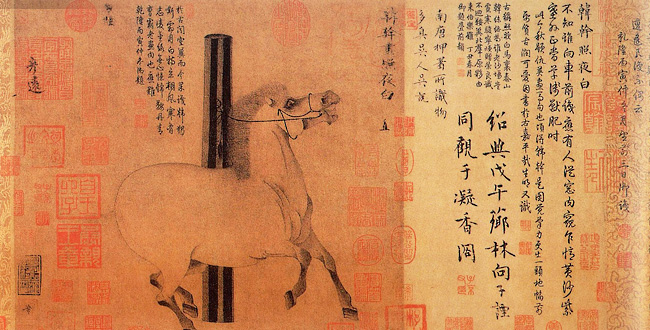

The ancient Chinese had tremendous fondness for these superior stallions. Emperor Wu personally penned an ode in their praise, and horses became a popular subject for painting and sculpture. One Tang Dynasty (618-906 C.E.) painter named Han Gan even made his name by only painting horses.

It wasn’t long before the horses themselves were invited to join the party. During the Han Dynasty, dancers stood atop galloping horses to perform tricks and tumbling techniques for admiring audiences. (Talk about taking classical Chinese dance to new heights!) Eventually, the horses themselves became the mane act. At court ceremonies, horse squadrons entertained the emperor by stepping, bowing, and marching to music in flawless formation.

This role was magnified during the Tang Dynasty, especially during the reign of Emperor Tang Xuanzong (the one who traveled to the moon in last year’s performance). Xuanzong had a 100 specially trained “dancing horses” for the royal court. They were decked in richly embroidered trappings, gold and silver halters, and wore precious pearls and jade ornaments in their manes. More elaborate costumes included phoenix wings and unicorn horns. Led by attendants in yellow shirts and jade belts, the horses shook their heads, swished their tails, and moved back and forth in time to music. Sometimes they were led atop three-tiered platforms to perform. Other times, they were given cups of wine, which they drank by picking up the cups and tilting the liquid back with their mouths. Each performance was enhanced by court musicians, drummers, acrobats, gold-armored guards, and backup dancers (elephants, in case you’re curious).

Of course, when dancing horses got too old, men and women in the emperor's court also entertained themselves with the latest fad from Persia: polo!

Horse-Class Mail (& Milk)

Fast-forward a millennium to the Mongolian Yuan Dynasty, and we see how, beyond the battlefield and imperial palace, horses also played important roles in everyday life.

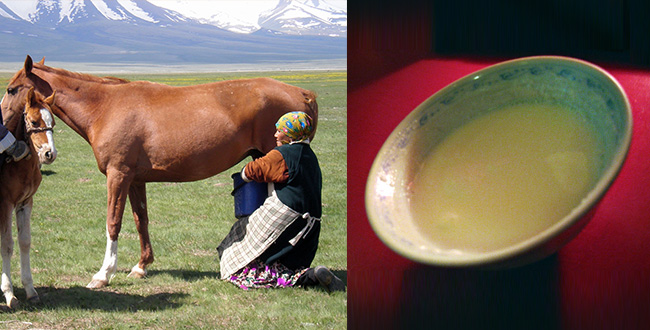

Mongolians and horses had long lived as partners on the vast grasslands. Mare's milk (also known as kumis) was an integral part of a nomad’s diet. Horseracing was the second-most popular Mongolian pastime (after wrestling), and horses played a key role in the Mongol conquest of the 13th century. Traditional Mongolian dance (as you may have noticed in our performances) includes movements that mimic galloping horses, as well as tricky footwork that imitates the movements of a rider on horseback. As the Mongolians themselves say: a Mongol without a horse is like a bird without wings.

Marco Polo, who visited China during the Mongolian’s reign, reported the empire’s extensive use of postal horses. This system was actually established during the Tang Dynasty. Messages were relayed from station to station with speed and efficiency. Perhaps the most famous client was Emperor Xuanzong himself, who ordered daily deliveries of fresh lychees to the capital from the southern provinces (more than 1,000 miles away, like ordering freshly picked oranges from Florida to New York) for his favorite concubine, Yang Guifei.

Red Hare, White Dragon

A pair of China’s most famous horses comes from two of its classic novels. The first, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, actually has nothing to do with romance—it’s an epic inspired by China’s history during the third century, following the fall of the Han Dynasty.

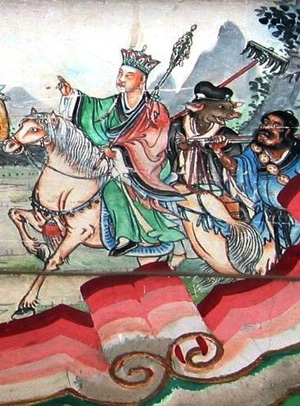

The adroit warrior Lü Bu and his horse Red Hare were renowned for their martial prowess. A saying recorded in the historical Cao Man Zhuan (曹瞞傳) described them as: “Lü Bu first among men, Red Hare first among horses.” In the novel, Red Hare could travel 1,000 li (about 260 miles) in a day, scaling mountains and fording rivers as if they were flat ground. This, while carrying his rider, an armored warrior that not only shot arrows and carried a spear, but wore a decorated headdress with three-foot-long pheasants’ tails. Though as red as his namesake, there is no evidence (historical or otherwise) that Red Hare had any rabbits up the family tree. Perhaps the inspiration came from the Energizer Bunny.

The second novel, Journey to the West, a Shen Yun staple, depicts the adventures of a Tang Dynasty monk and his disciples, the Monkey King, Pigsy, and Sand Monk, on their quest for Buddhist scriptures. Audience members familiar with the classic novel may remember that the Tang monk actually has one more disciple: a magical white horse that carries him on the long journey.*

Well, strictly speaking, he’s not really a horse, but a shape-shifting dragon—the third son to the Dragon King of the West Sea. After he accidentally destroyed a precious pearl his father received from the great Jade Emperor, the unfortunate son was slated for execution. The Bodhisattva, understandably known as the Goddess of Mercy, rescued him, assigning him the role of accompanying the Tang Monk on his journey—in the form of a horse.

His first meeting with the monk, though, was rather awkward. The dragon was hiding in a stream when the Tang Monk crossed on his (original) white horse. Failing to recognize his new master, the dragon ate the poor animal by mistake. Luckily, the Monkey King was able to beat some sense into him, and the dragon prince willingly took on the task of transportation. And really, when all your disciples can shape-shift, breathe underwater and walk on air, riding a dragon-turned-horse only seems like the norm.

A Stable Job

During one of his tenures in heaven under the Jade Emperor, the Monkey King actually held an official post as Protector of the Horses. His job was to look after the stables of the heavenly Cloud Horses. But boredom and idleness (the devil’s playground) soon led him to steal the immortal peaches in the royal orchard instead. Needless to say, he didn’t get to keep his job after that.

To make a long tail short, it’s been centuries since their glory days in the Middle Kingdom, but horses still hold a special place in China today—and not just during the Year of the Horse. In fact, the Chinese phrase for a prized steed, or 寶馬(bǎo mǎ), shares the same name as “the ultimate driving machine”—BMW. Now, that's horsepower for you.

* We’ve come close to depicting White Dragon Horse’s story on stage, but never taken the plunge. Last year’s Journey to the West-inspired dance did feature a river—but it was Sand Monk’s hideout, not dragon horse’s stream. And this year’s Ne Zha includes a Dragon King and his undersea palace—but this is a different family of dragons. Maybe our flying horse-hero will make his debut in the future? I hope so. He’s apparently quite the skilled swordsman (or woman, depending on circumstances) in human form.

Jade Zhan

Contributing writer

February 4, 2014