Interview with Shen Yun Symphony Orchestra Composer Gao Yuan

At the headquarters of Shen Yun Performing Arts in New York, around the clock the sounds of rehearsal are issuing from every studio. Shen Yun's musicians are particularly busy. In addition to preparing to accompany the 2019 dance production, they are perfecting their collaboration for the Symphony Orchestra fall season.

It wasn’t easy, but we managed to track down one of our busiest—composer Gao Yuan—to give us some unique insight into what to expect from this year’s concert.

Q: Could you explain how our Symphony Orchestra is different from our other annual production?

GY: In the regular Shen Yun performance, dancing takes center stage and music is accompaniment. For the concert tour, we combine Shen Yun’s touring orchestras into a full symphony orchestra. Our music gets the spotlight and we go all out to create the most magnificent musical experience we can.

The program’s original selections are taken from our dance performances’ all-time favorite pieces. We then rearrange them for our full symphony orchestra. The melodies you hear in these compositions were inspired by ancient folk and ethnic tunes that have been passed down through the ages.

The Chinese instruments you’ll see in the center of the orchestra play the melody against the backdrop of a full orchestra. So you’ll hear the grandeur of the Western symphony, along with the unique, ethnic infusion of traditional Chinese instruments. The trick is how to get them to play in seamless harmony.

This idea of using Western orchestral arrangement to present China’s 5,000 years of culture and music is new and hadn’t been done before. And we explore a range of China’s distinct dynasties and ethnic groups. So what you will experience is a vivid cross-cultural production.

Q: What are some of the highlights in the history of Chinese music?

GY: From excavated instruments, we know that Chinese music dates back over 9,000 years. Over time, four genres developed: folk, literati, religious, and court music.

During the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E.-220 C.E.), the court established an imperial bureau known as yuefu, which took charge of musical education as well as collecting ancient folk music and poems. Culture exchange with western Asia back then also introduced new instruments to the Han. This led to even more advances in Chinese music.

Then, during the Tang Dynasty, Emperor Xuanzong (reign 712-756), who was a talented musician himself, created and personally supervised the Pear Garden imperial music academy. The institutions he created trained professional performers, and contributed immensely to the development of Chinese music.

Q: There is an old belief, now being revisited, that music has the power to heal. Where does this idea come from, and how does it apply to traditional Chinese music?

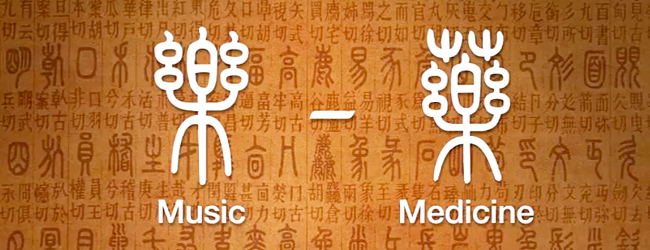

GY: Our ancestors believed that music had the power to harmonize a person’s soul in ways that medicine could not. In ancient China, one of music’s earliest purposes was for healing. The Chinese word, or character, for medicine actually comes from the character for music.

During the time of the Great Yellow Emperor (2698–2598 B.C.E.), people discovered the relationship between the pentatonic scale, the five elements, and the human body's five internal and five sensory organs. During Confucius's time, scholars used music’s calming properties to improve and strengthen people’s character and conduct.

Today, scientific research has also validated music’s therapeutic ability to lower blood pressure, reduce anxiety, enhance concentration, stabilize heart rate, and more.

Q: One of the most unique aspects of Shen Yun music is that it uses both Chinese and Western instruments. Which Chinese instruments can we expect to see on stage with the Symphony Orchestra?

GY: Our orchestra includes bowed and plucked Chinese instruments, as well as a many Chinese percussion instruments.

The erhu, sometimes called the Chinese violin, is a bowed instrument with only two strings. But even though it has only two strings, it can deliver the richest, most somber sounds.

The plucked pipa, also known as the Chinese lute, was a favored instrument in the imperial palace court.

Our percussion section also includes a range of Chinese cymbals, Chinese drums, pengling bells, chime bowls, and gongs.

These historic instruments have played vital roles in Chinese music for thousands of years. They’re very representative of traditional Chinese culture, its customs and spirit.

Q: What are some of the challenges that composers and musicians face in creating this performance?

GY: The compositions were all originally dance accompaniment, so at the time of writing these pieces, our job as composers was to collaborate very well with choreographers. We tried our best to make their visions a reality. Our work was not completed until the music satisfied every last detail of the dance, and this was sometimes well into the rehearsal period. For this concert, we had to revise the pieces to fit a symphony orchestra performance in which all images will be painted through music alone.

Q: What do you hope our audience will take away from the concert?

GY: I hope they will be inspired. Inspired by beautiful melodies, inspired by the performance’s energy, inspired by China’s ancient culture, and inspired by a new development in classical music.

* * *

Shen Yun Symphony Orchestra also pays tribute to celebrated works from Western classical music and features award-winning vocal soloists who are reviving the art of a lost vocal technique.